Final Frontier: The Road of a Million Bones

Snaking through Russia’s wild and unforgiving Far East, small towns dot an otherwise barren and lunar landscape. A single road, the Kolyma Route, connects the furthermost outposts of the former Soviet empire. But, the road is also known by a more sinister name, the ‘Road of Bones’.

A Soviet gold rush

At the turn of the 20th century, gold and platinum were discovered in the Kolyma region of Siberia. Under one of Stalin’s famous five-year plans, the USSR was going through a period of rapid industrialisation. Mining the region’s wealth meant that the state would be able to finance economic development across the rest of the Soviet Union. Inaccessible and cut off from the rest of the world, a vast highway was proposed to transport miners and minerals.

Construction began in 1932. Hundreds of thousands of political prisoners and convicts began working on a 2,000km stretch of highway from the Russian port city of Magadan on the Pacific Ocean, inland to Yakutsk, the capital of the Yakutia region in eastern Siberia. It would take 20 years to complete.

One death per metre

The prisoners hacked their way through insect-infested sweltering swamps and far-flung frozen fields using just shovels and wheelbarrows. According to one camp commander, Naftaly Frenkel, "we have to squeeze everything out of a prisoner in the first three months, after that we don't need him anymore." Tens of thousands were shot for not working quickly enough, while hundreds of thousands more froze to death in temperatures as low as -50C. It’s estimated that up to one million died building the road, one death for every metre of road built. Their bodies were simply buried into the road’s foundations.

The highway is mostly unpaved, and covered with a mix of dirt, gravel and sand. Driving on it was only feasible in summer or winter, when it was completely dry or covered in ice. In spring and autumn, it became too muddy. Authorities installed shipping containers with heaters and two-way radios, and made it illegal to pass a stranded vehicle without stopping. Even today, breaking down during winter almost certainly means freezing to death.

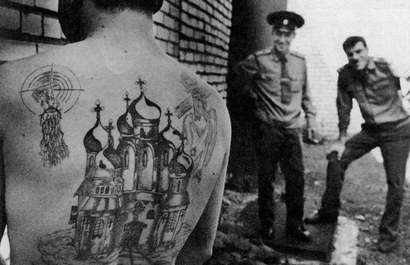

The very real human toll

After the road was finished, hundreds of thousands more prisoners traversed it. Many were ordinary convicts, but most were political prisoners, victims of Stalin’s Great Terror. The rocket scientist, Sergei Korolev, regarded by many as the father of modern space travel, was sentenced to death and sent to Kolyma where he lost most of his teeth. He was later rehabitied and led the development of the Soviet rocket program, launching the first dog, Laika, and human being, Yuri Gagarin, into space.

Nikolai Getman, a Ukrainian poet who spent almost 10 years building the road said of Kolyma "some may say that the Gulag is a forgotten part of history and that we do not need to be reminded. But I have witnessed monstrous crimes. It is not too late to talk about them and reveal them. It is essential to do so. Some have expressed fear...that I might end up in Kolyma again—this time for good. But the people must be reminded... of one of the harshest acts of political repression in the Soviet Union."

Today, the road is treated as a memorial to those that lost their lives. In the early 90s, a statue called the Mask of Sorrow was erected to commemorate the suffering and deaths in Magadan, at the start of the highway.